Fishermen and windsurfers call it weed, but eelgrass (species name Zostera marina) is actually not a simple, algal seaweed. It's a seagrass, an evolutionary descendent of complex land plants with real leaves and roots. Eelgrass' roots let it live on soft sand and mud, creating a structural habitat where there would otherwise be nothing. The species Zostera marina is widespread in the Northern Hemisphere but is at its Southern limit in Virginia and struggles during our hot summers. In other parts of its range, like the clear waters of California's Channel islands, it grows deep down where you have to scuba dive to get to it. I showed this picture in a talk I gave at the Western Society of Naturalists meeting, not knowing who the random diver was. It turned out to be a guy in the audience!

In the cool, damp Pacific Northwest, eelgrass can survive being exposed to the air at low tide. I remember seeing eelgrass on the sand flats when I was a kid digging for razor clams in Birch Bay, Washington.

In Chesapeake Bay, eelgrass is confined to the narrow area just below the low-tide line. Here, Matt Whalen from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science is pushing a net to catch crabs and stuff living in the grass.

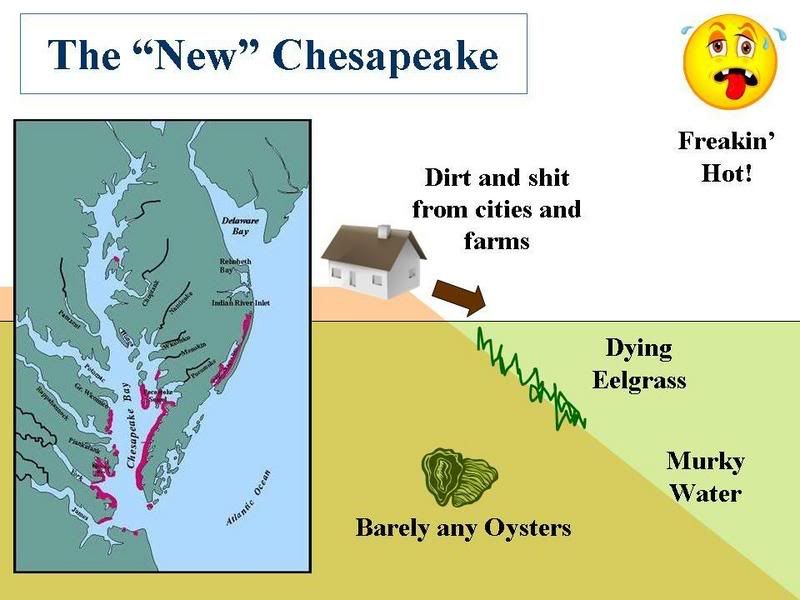

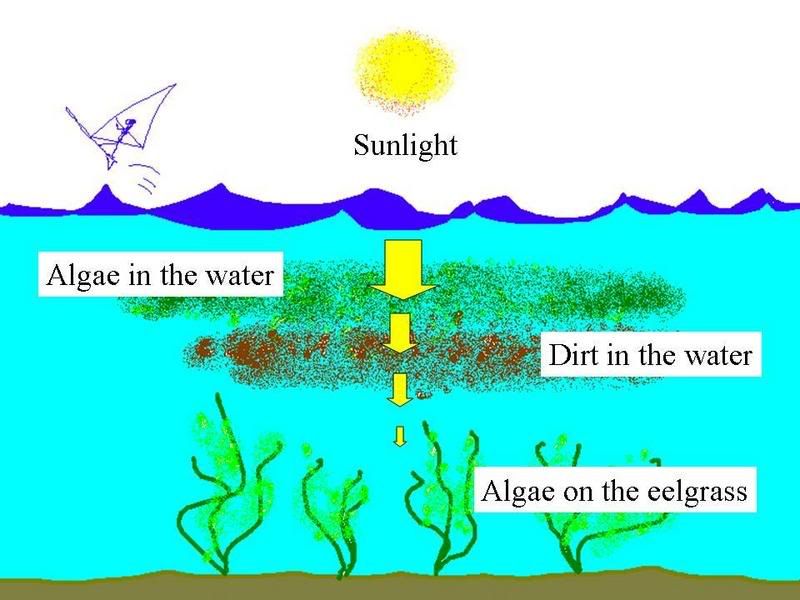

The diagram below shows why eelgrass can only inhabit a narrow depth range in the current Chesapeake Bay.

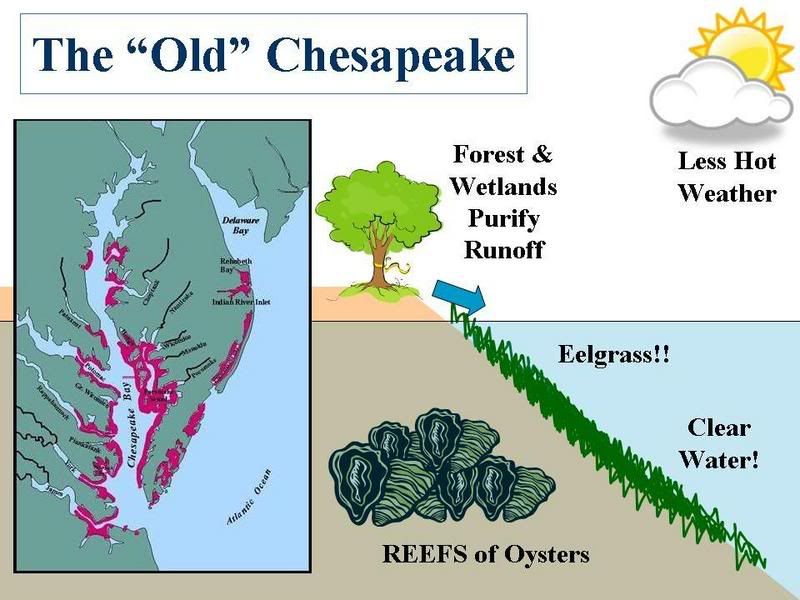

Basically, the water is too murky for eelgrass to grow down deep, and it's too hot for it to grow really shallow. It wasn't always like that, though. Before the middle 20th century the water was clearer and eelgrass was able to grow down deeper, covering a much greater portion of the Bay.

What makes the water murky? It's a couple different things. Algae in the water (aka phytoplankton) turn it greenish and block out much of the light. Dirt in the water (aka suspended sediment) makes it a muddy brown and blocks out still more light. As a final insult, algae called "epiphytes" grow directly on top of the eelgrass and steal whatever light is left.

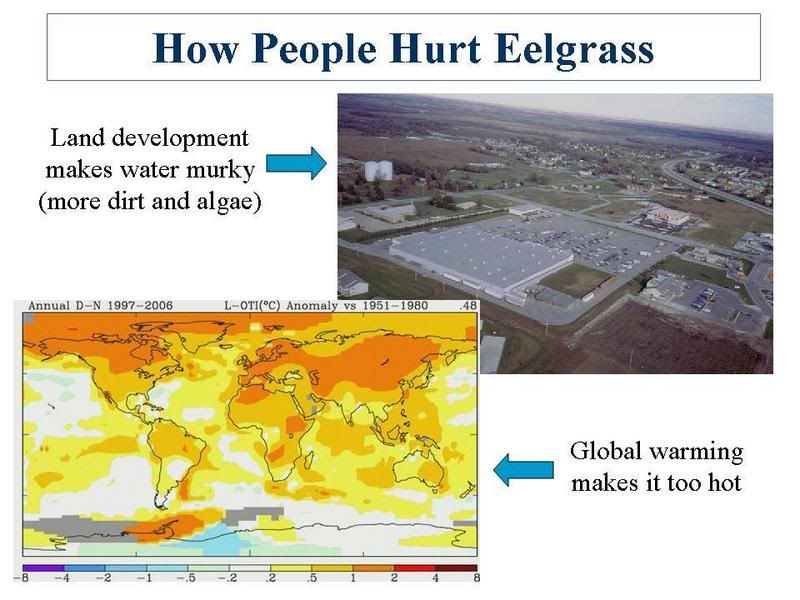

Human activities on land can result in more algae and dirt in the water. Sewage and runoff muddy the water directly with the sediment they contain, but also make the water murky indirectly by fertilizing algae. When algae run wild from exessive fertilization, it's called "eutrophication". Besides making the water murky for seagrass, eutrophication is responsible for "Dead Zones" where rotting algae remove all the oxygen from the water and make it uninhabitable for fish and crabs.

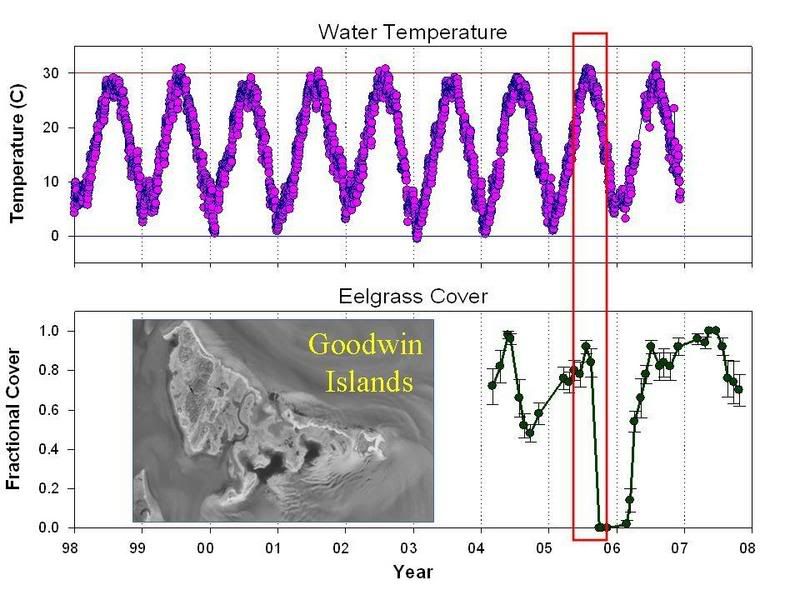

On top of that, the effects of global warming on eelgrass are already starting to be felt. There is always a bit of a decline in eelgrass during the hottest part of the summer, but in 2005 it really got hammered by an unprecedented number of days of water temperatures over 30 degrees celsius. The data below are from monitoring that VIMS does at Goodwin Islands, a nearby nature reserve that used to be surrouned by eelgrass beds, but now has just a few bits left (dark coves on the Southeast side). The red box highlights where the hot summer knocked out eelgrass. Though it came back in 2006 at Goodwin Islands, other spots in the Bay still haven't recovered.

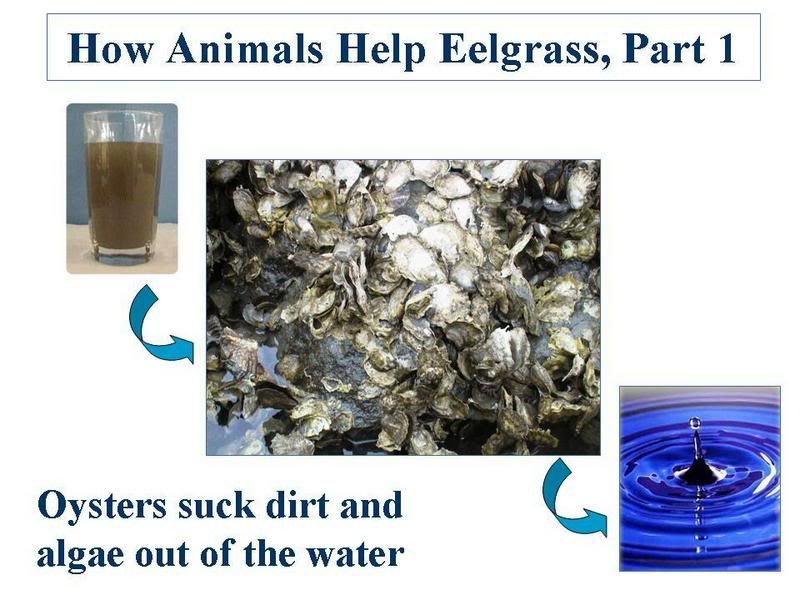

I've been concentrating on the bad news, but there are some hopeful things I should mention. For example, some animals in the bay might be able to help eelgrass recover. Oysters are filter feeders that clean and clarify the water. They used to be so abundant in the bay that they formed massive reefs, and their collective filtration significantly improved water quality. If we could bring them back to that level, they would reduce the impact of the excess sediment and nutrients that human society dumps into the water.

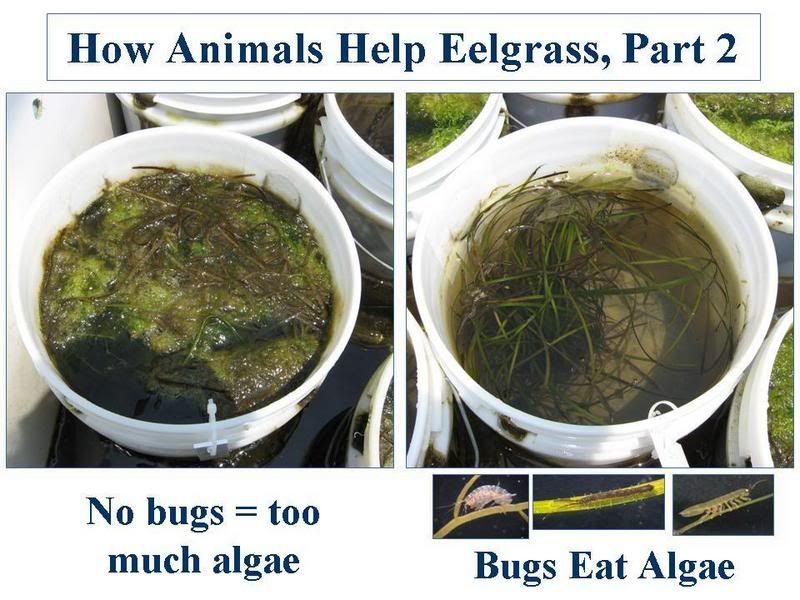

Another group of animals is important as well; the little bug-like things that eat epiphytes, the algae that grow on top of eelgrass blades. Some recent experiments have shown that these bugs are just as important to the health of eelgrass as is clean water.

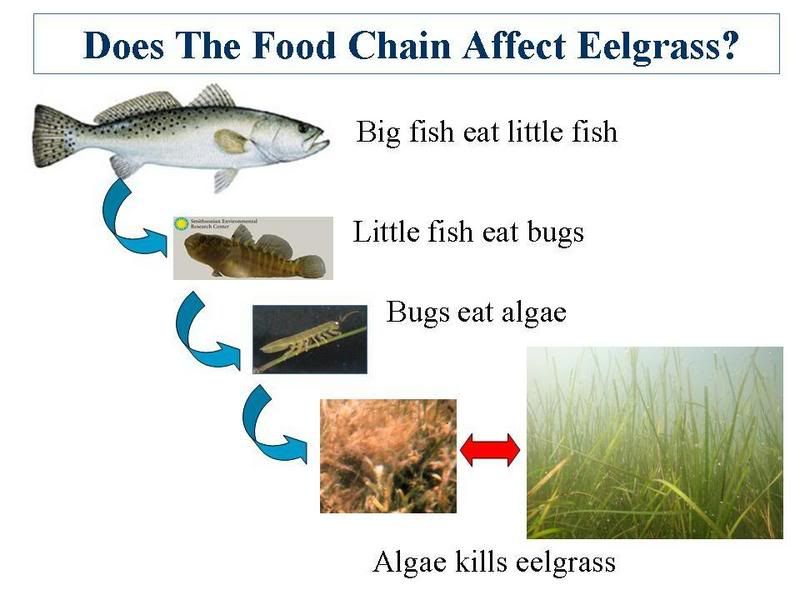

That brings up an interesting question- what controls the abundance of the algae-eater bugs? We know that they're connected to other animals in the bay through the food-chain, so it's possible that changing the abundance of big fish could indirectly affect the abundance of algae-eaters, with serious consequences for eelgrass.

With all these different things affecting eelgrass, what should we do to save it? Well, I think we should try a diversified strategy. On land we should try to limit urban sprawl and preserve as many forests and wetlands as possible to keep dirt and excess nutrients from entering the bay. We can advocate for better farming practices so farms don't release as much fertilizer and sediment, and we can eat less meat so we don't need as much farmland in total. It will also help to have more trees and natural vegetation around houses, roadsides, and streams. In the water, we should make protecting and restoring oysters a number 1 priority, even if that means stopping all oyster harvesting and shifting to oyster aquaculture to provide oysters for eating. As for the algae-eating bugs, we need to learn more about the Chesapeake Bay food chain to find out the best way to protect them. Last but not least, we need to stop and reverse global warming. That means conserving energy, driving less, recycling, and voting smart. If we do all this, the future Chesapeake Bay may regain the eelgrass beds and oyster reefs of it's pre-20th century glory. :)